Some books are that fabulous combination of great non-fiction that supports topic learning and an enticing and engaging book that children will read for pleasure… cue Hugo D Cook’s Tales of Ancient Egypt. Hugo, an Egyptologist who shares educational videos detailing history, culture and writings from Ancient Egypt, has curated a selection of particularly interesting yet lesser known (along with the more familiar) stories into a collection that will fascinate readers!

A great addition to KS2 Ancient Egypt topic boxes, readers will find facts, myths and striking illustrations, Hugo has very kindly answered some questions about what’s in his book, how he created it and what he hopes readers will find inside…

:

Hi Hugo. Could you start by telling us a little about yourself and what you do?

Sure! I’m an Egyptologist – still a fun thing to say – so I work on various things to do with ancient Egypt. For me that involves a mix of teaching people how to read hieroglyphs as a lecturer, creating informative displays in museums, writing and editing articles for publications, helping to make documentaries, working on interesting research, and more. I adore it!

Tell us a little about the book. What kind of tales are inside?

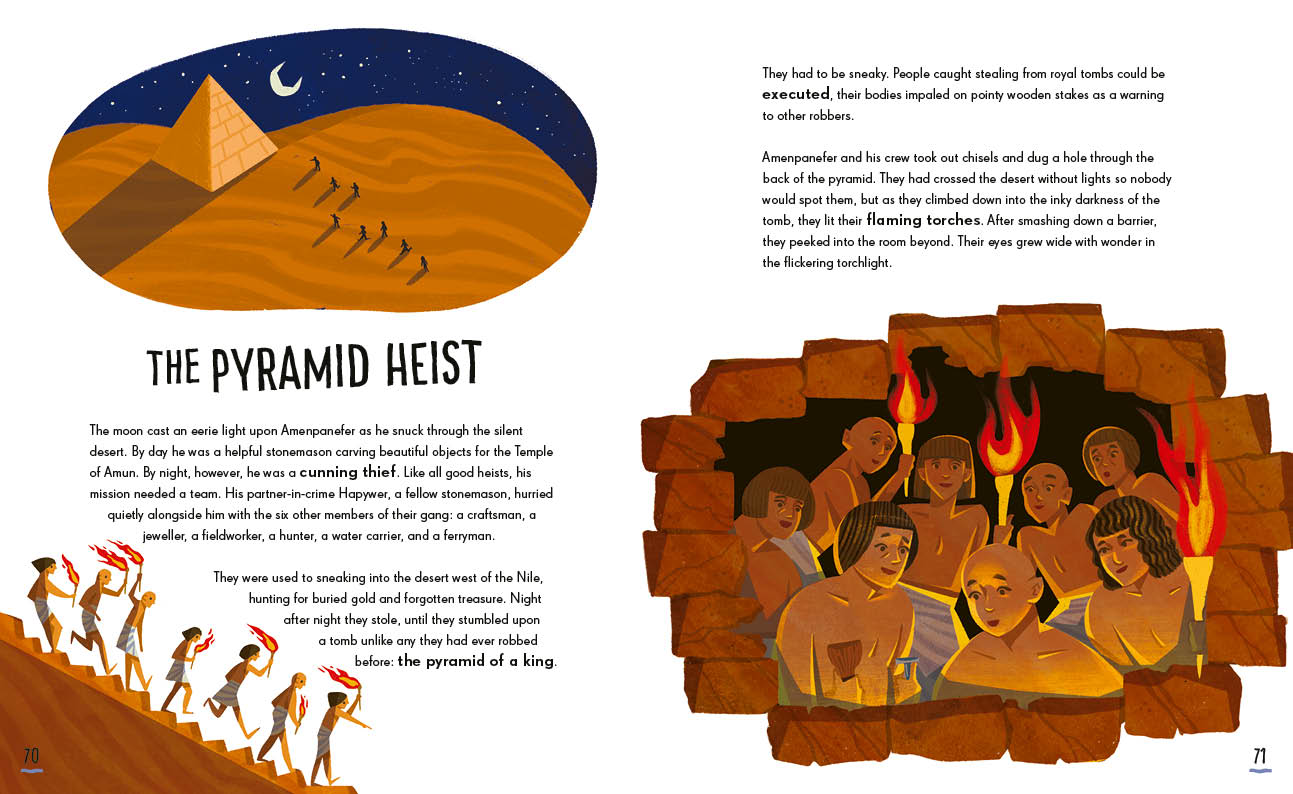

It was a brilliantly fun book to write. It contains about 60 or so ancient Egyptian stories – more than any other children’s book I know of – and these wonderful tales are brimming with magic and mayhem, danger and deceit, love and laughter. Excitingly, many of these stories have never before been translated and published like this for non-academic audiences, so they will be new to even devoted Egyptology aficionados. For example, one of my favourites is the true story of some ancient tomb robbers. In the 11th century BC, one of them gave a dramatic testimony in court – and I thought this incredible first-hand account of the heist would make for a perfect children’s story. When I mentioned it to the publishers, I called it Ocean’s 11th Century BC, which sadly nobody laughed at. In the testimony and in the story, this tomb robber talks about how he assembled his gang of specialists, how they found an even-more-ancient pyramid, how they stealthily broke in, and what they found inside. That bit is particularly exciting, as of course all the pyramids have been looted by today so it’s breathtaking to hear one of the only accounts of the treasures they once contained. Maybe my favourite bit of that story is how the robbers, rather than rifling through the king and queen’s mummies to find the little golden amulets buried inside their bodies, saved time by setting fire to the mummies instead so that they could easily pluck said amulets out of the resulting piles of ash! That’s one way to go about it I suppose. What happened next, and how this robber ended up giving a court testimony… well, no spoilers. I think that example shows that great stories aren’t just found in big mythological texts, but you can even dig up gems in things like court documents. That said, I included many a myth too. So I managed to find lots of stories that will be new to readers, like Egypt’s only original story of a walking-talking mummy, as well as adding some refreshed classics like the story of Cleopatra.

Did you translate these ancient stories from the Hieroglyphs yourself?

Yes, I took every story from the original text using my own translation; but not just from Hieroglyphic Egyptian. I also used Latin, Greek, and other ancient Egyptian languages called Demotic and Coptic. Once I’d made my translation, I then paraphrased it to fit the word count, to make it make sense to another culture, and to edit anything inappropriate for the 8-10 age range (you know what ancient myths could be like…). That said, I kept things like dialogue nice and original. I think this translation- and text-based approach was important, especially for the famous stories in there like Cleopatra’s. In the past these stories have suffered from a bit of a Chinese-whispers effect, where someone has written something based on an English version they read which was in turn based on another English version and so on, and it can lead stories quite far away from the original. So, for example, my version does mention the famous Shakespearean account of Cleopatra’s carpet hideout, but I mostly used the earlier description of that carpet in fact being a bed sack.

What made you want to be an Egyptologist? Did learning about it at primary school have any effect?

Absolutely, primary school was lifechanging for me. I had always been interested in ancient myths and stories: the first book that was read to me and that I grew obsessed with was Atticus the Storyteller, a book of Greek myths not dissimilar to my book. But I can tell you the exact spark that set off a lifetime love of ancient Egypt: I was in Year 3, and everyone was learning about Egypt. It’s that period when every child in the country is obsessed with all things Egyptian, and I was one of them. The real spark moment, however, was a homework assignment to build a model shadoof, a type of Egyptian water crane. I can remember it so vividly to this day, tilting my model up and down to lift the blue marbles (my Nile water). I remember thinking how amazing it was that something so clever had been built thousands of years ago. The next year came, when all the children move on from their Egypt phase onto the Romans or something, but my sense of wonder I had felt looking at that shadoof refused to die. Each year my interest grew and grew, and I read more and more, until I got into Oxford to study Egyptology and people realised it wasn’t just a childhood phase.

What is the state of education on ancient Egypt? How do you aim to contribute?

It’s funny, we have more written sources from ancient Egypt than we do from the entirety of medieval Europe combined. Despite this huge wealth of information, however, very little is disseminated to the public. You see the same stories done again and again and again. A few years ago I was helping with a documentary, and a major broadcaster asked the producers to do another series on the ancient world. When I suggested some really fascinating topics that I thought would teach people lots of interesting new things, the broadcasters said no, as they wanted familiar topics like Julius Caesar so the audience could say “Ha I knew this” rather than “Wow, that’s amazing.” It was in that moment I realised the state of historical dissemination was in shambles, and I decided to work on showing people the millions of hidden wonders of the ancient world. I hope this book can help break down that barrier and let teachers, parents, and children access some of these wonderful stories.

This book is stunningly illustrated. What was it like working with an illustrator for that?

It was incredible, I want to do it again now. Sona Avedikian, the marvellous illustrator, did such a wonderful job. Her style is incredibly charming and has an almost magical quality to it, despite its historical accuracy. She was brilliant at dealing with all my nitpicking requests for this enormous volume of images she created. Honestly, I think I probably spent more time working on what should be illustrated than I spent writing the actual text, because if a picture tells a thousand words, then it takes a thousand words to describe what a picture should look like! It was a fun challenge to describe, for example, a dragon-filled region of the underworld just based on ancient written descriptions so that Sona could visualise it in breathtaking colour. Alexander the Great’s funeral carriage took pages of details! You quickly realise that far more details need to be given than just showing the design team a picture of what, say, a certain god looked like in ancient art. For example, a draft illustration of the sun god Ra had to be edited because his crown had a snake on it, as it usually does in ancient depictions, but this page’s myth takes place before the supposed invention of snakes – so the serpent had to go! I was blown away by Sona’s work. It’s not only beautiful, but also very special because, in the Egyptian mindset, having oneself preserved in the living world was essential for the immortality of the soul and a perfect afterlife. While usually that took the form of preservation by mummification, they also believed preservation in art (and in writing) did the same. That form of legacy is one of the reasons for all the amazing monuments they made, though with so many having been lost over the millennia, including the mummies of many people in this book, it would be quite relieving for them to know their form and image survive through Sona’s work. Commoners like those tomb robbers would never have dreamed of getting this gift for the first time in over 3,000 years. What would they say, I wonder, if they knew that their names and images are now circulating through lands they didn’t know existed? That children around the world will learn their names, hear their stories, see their faces? It might have mattered more to them than all that gold they stole, if only we could tell them. In the Egyptian mindset, this sort of illustration quite literally ‘brings them to life’, without metaphor. Pharaohs waged wars and raised pyramids to preserve their legacies like this. It’s very heartwarming to look at this book and think about how it enshrines the memory of kings and commoners alike. I hope they’d be happy with it, and I hope this book helps today’s children widen their eyes at the wondrous world of ancient Egypt. Wouldn’t that be wonderful!

You can read more about Hugo’s fascinating and fantastic tales, and special discounts for schools, by clicking the image to the left.

Who knows, your classroom may be home to the next Hugo whose thirst for knowledge and understanding of Ancient Egypt starts with your topic learning and never goes away!

~

Thank you Hugo for sharing your answers and for curating these stories students might not ever have come across otherwise.