If being a teacher showed me anything, it’s that children, like adults, are each an individual with infinite depth. For the children who aren’t LGBT+, seeing characters who are with struggles unrelated to their identities normalises what is, frankly, normal. Growing up without this creates an inaccurate perception that LGBT+ people are ‘other’. We become viewed – through lack of visibility – as at best a novelty and at worst a threat. Children deserve better: to see diversity, and how natural (and often inconsequential) it is.

For the children who are LGBT+ or questioning, feeling as though you are the ‘other’ is a burden worsened by never being represented. A big factor in children’s happiness is seeing people like themselves existing in a state of acceptance, be that in real-life or fiction. Every child deserves to feel that who they are is an unshakable and welcomed part of humanity.

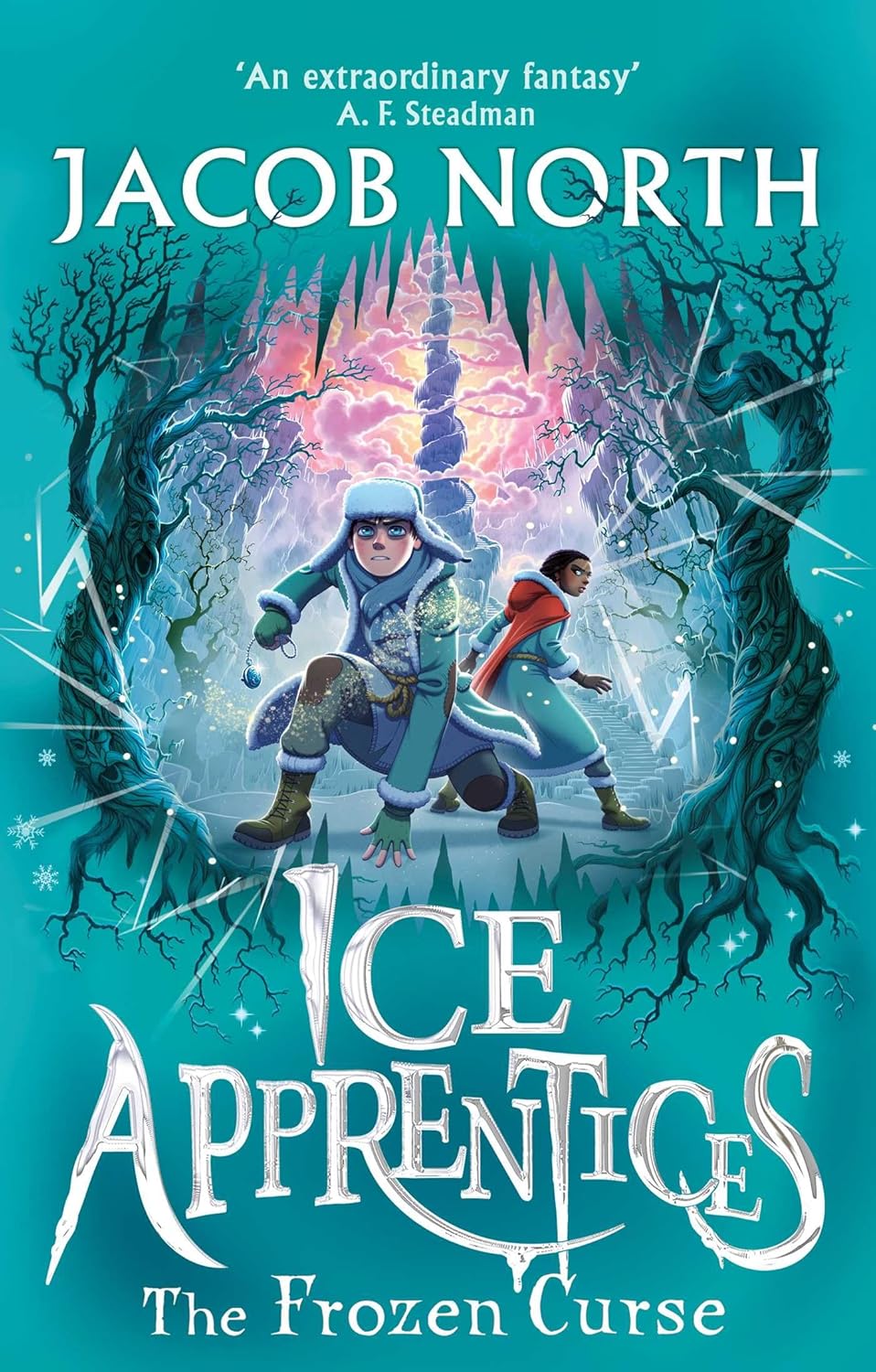

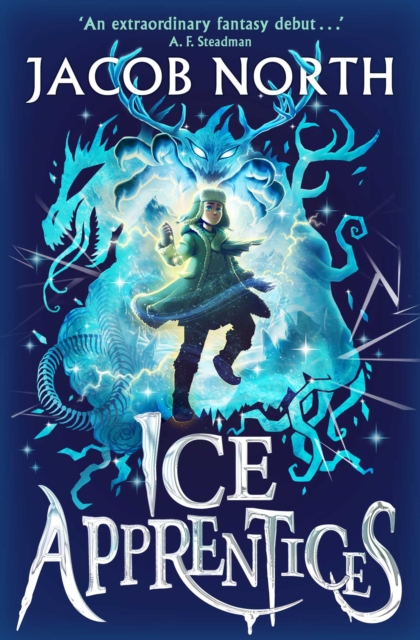

This is why, when I write LGBT+ characters, it is rarely issue-driven. If Oswin’s adventure in Ice Apprentices was issue-driven, his struggles would centre facing transphobia. He’d be misgendered, bullied, and excluded from spaces. These are real issues children who don’t fit rigid gender roles face, which compound for those who are transgender or non-binary. Books examining these heavy topics play a vital role on any shelf: fantastic for working through or growing an understanding of upsetting situations. But when I am lucky enough to find a book with a transgender character, I love when their struggles are unrelated.

When it comes to the day-to-day life of transgender people, all sorts of obstacles and aspirations apply (and are often more prominent) than them being transgender. If we only have issue-driven stories, readers gain the impression that characters with identities considered ‘none-default’ exist solely to explore having said identity. It builds an expectation that LGBT+ identities can only be a mechanism to examine LGBT+ struggles, and never an incidental part of a person. This makes said characters face an uphill battle of ‘making it their entire personality’ when their identity is the focus and ‘not being necessary for the story’ when it isn’t. A gay character doesn’t need a dealing-with-bigotry storyline to justify being written as gay.

Stories that aren’t issue-driven show LGBT+ identities don’t need justification, while issue-driven books provide catharsis and understanding. Both are important. Having one and not the other is a crying shame. Fortunately, I’ve yet to see a bookshelf without space for both. Tragically, plenty don’t have either.

With this in mind, how does Ice Apprentices approach LGBT+ representation? Quite simply, it shows there are all sorts of identities, and none are more noteworthy than others. Reginald and Ferdinand, a sentient fence and gate, are beloveds. It’s mentioned when relevant, and no one bats an eye. Philomena having two dads is received the same as Maury having a mum and dad. The non-binary Master Tybolt uses they/them pronouns with the same lack of fanfare as the cisgender Grandmaster Yarrow using she/her. Everyone treats all of these as equally ordinary because they are.

In Ice Apprentices I approached LGBT+ characters the same way I did none-LGBT+ characters: aiming for depth of personality. Oswin has feelings of gender dysphoria, but these take up a handful of sentences. They are a part of the lens through which he sees the world, but a small one. More notable is his insatiable curiosity, goofy humour, and obsession with being useful. There are plenty of books which celebrate and focus on LGBT+ identities. In a world that puts them down, this couldn’t be more needed. Alongside these, it’s lovely to have stories showing how de-centred being LGBT+ can be to someone’s adventure. To display the equally wonderful mundanity of both being LGBT+ or not being LGBT+.

Readers will know Oswin is transgender. But if asked to describe him, my hope is this would not be the first thing to spring to their minds. I wanted Ice Apprentices to show not just how plenty of people are LGBT+ but that, crucially, we’re people first, with all the depth that entails.